Transformative Practices

The following practices were undertaken under the broad umbrella of TRULAB and its collaborators from all over the world. The common theme running through all these practices is to foster transformation through a wide range of creative and practical strategies. These are are not presented as perfect examples or best practices. Rather, in the spirit of experimentation described by the philosophy of Pragmatism, they embody the actual testing of transformative ideas on the ground and subsequent reflection for developing powerful practices.

Harnessing the Power of Design Concepts: India: 2016 - 2017

How can design concepts become powerful tools to execute projects in politically savvy ways?

Within design practice, concepts can be extremely powerful tools for coming up with innovative ideas for projects, including in working with clients, fellow professionals and even public authorities. Design concepts often develop in a non-linear fashion as part of the design process and involve many different strategies to address a specific problem. Working with them involves finding or creating an internal logic for the project out of the program, the conditions, the materials, or maybe some combination of sensibilities.

The goal was for participants to take these ideas and incorporate them into their own practice to make it more effective. This project was in fact initiated by and involved well-established practitioners in India from a wide range of fields, including architecture, interior design, landscape architecture and urbanism. Workshops were held in the cities of Jaipur, Pune and Surat from 2016 to 2017. Participants were asked to analyze readings and case studies and to actively contribute their own knowledge, experience and perspective. Thus, each workshop was conceived as an interface that enabled participants to develop their own creative and critical thinking on design concepts. In general, participants--including financially successful ones--were hungry for new conceptual ways of thinking about designing processes and projects in order to be more effective.

The case studies analysed included Säynätsalo Town Hall [1949-1952] by Alvar Aalto in Jyväskylä [Finland], Centre Pompidou [1971-1977] by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers in Paris [France], India Habitat Centre [1988-1993] by Joseph Stein in Delhi [India] and Nova Icària / Vila Olímpica [1986-1992] by MBM Puidomènech in Barcelona [Spain]. Whether the main task was to design a program and the management of spaces and activities, a long-term development of the project through a clear regulating plan, or a building that is fundamentally representative of the notion of democracy; in these cases, design concepts became powerful as they are embedded in the complex relationships between architecture and urbanism. For example, large-scale urbanism projects tend to have more complex interpretations and manifestations of the design concept, which can be realized through a variety of long-term mechanisms, such as proactive design guidelines, easy-to-understand building codes, and a clear regulation plan.

Collaborators: Sanjeev Vidyarthi and Aseem Inam.

Designing New Practices with the Thorncliffe Park Women’s Committee: Toronto: 2016

How does one craft an open-ended urban practice?

The vast—if not all—projects in urbanisms are usually highly defined: starting with a client, a site, a program, a budget and an expected outcome; an approach that aims to be clear and to have shared expectations. However, experience demonstrates that even the most comprehensive and precisely defined project never turns out the way it is designed. There are long time frames, changing circumstances, conflicting interests between multiple stakeholders, and sometimes uncertain and surpassed budgets. In this context, it serves to pursue more open-ended, flexible and adaptive approaches to practice, conducting serious and systematic research from the very beginning as an integral component of the design process. In this approach, understanding a situation and strategizing about its future inform each other on an intertwined and ongoing basis.

The experiment in Thorncliffe Park was designed as a one-year collaboration between the University of Toronto Department of Geography and Planning, the Thorncliffe Park Women’s Committee, and the residents of the neighborhood. Rather than a client brief or a given problem to be solved, the starting point in Thorncliffe Park was what the community had already accomplished through their own initiative and informal urbanisms. We spent a great deal of time in on-the-ground research and community dialogue, and we built upon already-existing informal strategies [e.g. volunteer networks and community organizing, informal economies and the sale of goods and services by residents, and informal designs such as public space furniture, temporary structures and community gardens], to propose projects that served both as means as well as ends. Scholar-practitioners interviewed volunteer members of the Thorncliffe Park Women’s Committee to learn about their concerns, aspirations, resilience, resourcefulness and as women and immigrants, the ways which they navigate the neighborhood as well as the Canadian system of governance.

Instead of proposing fixed interventions, we devoted our creative energies to designing a process of community collaboration and action, including community workshops [with activities such as storytelling, informative presentations, and brainstorming potential actions] that were integral to the design process. Scholar-practitioners presented their research to city officials and practitioners [e.g. Silvia Fraser, Manager of the City of Toronto’s Tower and Neighborhood Revitalization Program, and Ya’el Santopinto, Project Manager with ERA Architects], as well as the communities in the area to get their comments. The ultimate goal was for communities to not simply accept programs—however beneficial—that are imposed on them, but to negotiate benefits that are customized to their particular needs and aspirations, and better yet, to harness such programs to fulfill their needs through community-initiated processes. Thus, the project generated widespread community excitement and involvement, attracted the support of political leaders, and created both a spatial vision of the future as well as the process to get there.

Collaborators: Aseem Inam and University of Toronto Scholar-Practitioners: Lauren An, Anni Buelles, Kelsey Carriere, Stephanie Cirnu, Aviva Coopersmith, Maria Grandez, Kelly Gregg, Michael Hoelscher, Jonathan Kitchen, Maria Martelo Mesa, Noha Refaat, Mercedes Sharpe Zeyas, Andrew Walker, Louise Willard, Jennifer Williamson, and Frances Woo.

Agents of Public Space Lab: New York: 2014-2015

How is the agency of street vendors generated within the ambiguous conditions of the city?

Informal urbanisms exist in every city in the world, both in the global south and the global north. The purpose of the experimental and open-ended workshop in New York City in January 2015 was to investigate the actual nature and potentialities of informal urbanisms. This investigative approach was based on the premise of “research as practice,” where goals and outcomes emerged through engagement with street vending systems in Union Square in Manhattan. These systems simultaneously constitute as economic activity, as an animator of public space, and as part of a larger system of exchange and power [including political control, legal regulations, provision of supplies, nature of transactions, and design of carts and spaces].

To recognize the transactional nature of street vending, the researcher-practitioners shifted the discourse to Agents of Public Space [APS], which also includes street artists, performers, farmers, chess players, and other vendors who exist in the economic and social ecology of Union Square. This shift allowed for more inclusivity within the complex realm of street vending and explored further notions of language as urban practice. The key term here is agents, in which those who engage with various aspects of the street vending system—including undocumented immigrants—in fact possess agency in their work and in the city. To address the daily precarity of all these APS, it became important to shift strategies to include both impacts in the short term [e.g. designing interactive scenarios that lead to direct action and structural change], medium term [e.g. designing smart phone apps that provide critical financial and legal information], and long term [e.g. designing a public HUB at Union Square for mobilizing APS].

This mode of practice for designing agency was both investigative and experimental: instead of traditional clients, the team created project collaborators; instead of a fixed problem to solve, the team generated collective knowledge of critical issues; and instead of a predictable outcome such as policy recommendations or design of objects, the team identified key points of strategic intervention within street vending systems to leverage the city as a resource.

Collaborators from: Parsons School of Design & The University of São Paulo; Aseem Inam; Renato Cymbalista; Leandro Leão Alves; Darcy Bender; Travis Bostick; Jefferson Chicarelli; Nadia Elokdah; Belisa Godoy; Shibani Jadhav; Alexandre Lins; Gabriel de Alencar Novaes; Walter Petrichyn; Bruna Dallaverde de Sousa; Jasmine Vasandani; William (Sam) Wynne

TRANSFORMING CITIES: BRAZIL: 2014

What are creative strategies for transforming small and mid-size cities in Brazil?

The Serviço Brasileiro de Apoio às Micro e Pequenas Empresas [Brazilian Micro and Small Business Support Service, or SEBRAE] invited TRULAB Director Aseem Inam to design and lead a workshop entitled “Transformando Cidades: Estratégias Criativas e Impactos Significativos” for 40 mayors, government officials and business leaders gathered in Belo Horizonte. The goal of the workshop was to collectively brainstorm ideas and implementation strategies for transforming cities in Brazil.

Aseem Inam designed the workshop to be both creative and visionary on the one hand, and down-to-earth and feasible on the other. Each group of 10-12 participants began by brainstorming about their cities’ assets, such as natural [e.g. river], geographical [e.g. location], physical [e.g compact size], social [e.g. networks], cultural [e.g. unique traditions], economic [e.g. informal entrepreneurship], political [e.g. dynamic leaders], and other types of assets.

The second exercise was to find ways to leverage assets towards prosperity [e.g. through innovative programs, collaborative initiatives and social movements]. The final exercise asked participants to collectively create concrete steps for making transforming their ideas into reality [e.g. building partnerships, finding funding, legal mechanisms]. The workshop techniques and transformative strategies were designed to be ultimately adapted and carried out in the specific context of each participant’s city.

Collaborators: Aseem Inam (TRULAB), Fabio Veras, Mônica Segantini, and Mayara Rodrigues (SEBRAE)

Pier to Pier Lab: São Paulo: 2013 - 2014

How does one design emerging urban practices?

This project was a collaboration between Brazilian and American researcher-practitioners from Parsons School of Design and the University of São Paulo, and aims to understand the true complexity of the city: How is the ambiguous threshold between the formal (i.e. legally and financially sanctioned) and informal (i.e. extra-legal structures and unofficial modes of exchange) city created, expressed, and occupied? In addition, the project harnessed the untapped potential of informal urbanisms, especially the remarkable efficiency, resourcefulness, and social dynamics of the informal city.

In January 2014, the group convened in the Guarapiranga region of São Paulo. Definitive to this workshop was its unconventional, investigative framework from which emerged transformative urban practices. The team of researcher-practitioners imagined the reservoir as more than water infrastructure to include its role as the ultimate public space in the Guaurapiranga area and as a resource to be further leveraged. The team offered a series of designed public spaces, or praças frutantes, to serve the economically diverse community around the reservoir. The services were prioritized to meet the needs of local residents [e.g. health services], to radically improve the quality of life [e.g. economic opportunities for local vendors], to bring diverse groups of people from different income groups together [e.g. public boating and swimming education programs].

The experimental engagement prioritized an innovative approach: research as practice, in which practices emerged out of interactions with the region, with its inhabitants, and with the different team members. Through this emergent process, the team defined as its objective bringing different communities together using the underutilized water reservoir. The Lab thereby went far beyond the traditional designer-client relationship by designing practices that are truly collaborative and adaptive.

Collaborators from: Parsons The New School for Design & The University of São Paulo; Aseem Inam; Renato Cymbalista; Leandro Leão Alves; Jefferson Chicarelli; Rania Dalloul; Joy Davis; Matt DelSesto; Priscila Fernandes; Belisa Godoy; Sara Minard; Gabriel de Alencar Novaes; Alexander Roesch; Bruna Dallaverde de Sousa; William (Sam) Wynne

Catalyzing Change in Villages, Small Towns, and Peri-Urban Areas:

Mumbai: 2012 - 2013

Can design catalyze social change in India?

The non-governmental organization [NGO], the Aga Khan Planning and Building Service India [AKPBSI] organized a workshop and symposium in Mumbai in 2012 to develop strategies for leveraging design as a catalyst for social change in peri-urban, small towns, and rural areas of India. As a form of transformative practice, the event possessed three remarkable aspects: a welcome shift in focus from megacities to small towns and rural areas, the format of interactive brainstorming workshop combined with a more formal symposium, and for TRULAB Director Aseem Inam, an immersive field visit to a rapidly-changing village in Gujarat.

In particular, the Policy and Governance Workshop Group embarked on an original strategy of presenting the findings of their group as a theatrical skit regarding transportation strategies for the Kalyan Dombivali peri-urban area of Mumbai. The skit captured the audience’s attention and creatively highlighted key ideas, such as the complex process by which different stakeholders actually interact to produce change and the up-and-down, back-and-forth nature of urban policy-making in a democracy. The Group thereby illustrated how practice is essentially an ongoing conversation rather than a finished product.

The event was a powerful demonstration of how an NGO like AKPBSI can act in exceptionally nimble ways to convene a gathering of some of the brightest minds and pursue empowering strategies, without an overly rigid agenda. NGOs are attracting highly qualified practitioners who are committed to do the challenging work that private firms do not find profitable enough and that public agencies find too complex. NGOs are increasingly part of global collaborative networks that benefit from an exchange of ideas and experiences across international boundaries and from cooperation on common challenges such as housing, infrastructure, and different patterns of urban growth.

Collaborators: James Wescoat (MIT), Surekha Goghale (AKPBSI), Aseem Inam (Parsons School of Design), Anna Heringer, EMBARQ India, IDEA, Dalberg Global Development Advisors, Thinking Green, D. Y. Patil College of Architecture, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Balwant Sheth School of Architecture, and the Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology.

Framework for Housing Reconstruction: Port-au-Prince: 2010

What is an effective recovery strategy after a disaster in one of the poorest countries in the world?

Following the devastating earthquake that struck Port-au-Prince, the Government of Haiti invited a team of researcher-practitioners to design a housing recovery strategy. The aim was to address the loss of an estimated 200,000 homes destroyed in the earthquake and the previous deficit of approximately 1 million homes. The team focused on medium- to long-term strategies that would take anywhere from a few months to a few decades to implement, since the urgent need to shelter the homeless and building temporary housing was already being addressed by other organizations.

The immediate task that the team undertook was to understand the conditions on the ground through site visits and documentation, data analysis, and most of all informal conversations, interviews, and focus groups with community members and leaders, non-profit organizations, private investors and developers, and government agencies. Through this iterative process, the team developed the following principles of recovery strategies: resilience to future disasters, equitable distribution of resources, broad-based partnerships, building for economic development, security of housing, and asset-based planning.

The multi-pronged set of strategies for housing recovery tackle the following task areas: land use and master planning, building codes, construction materials, transitional pre-fabricated housing, housing finance, household energy, household water and sanitation, waste management, and institutional arrangements [e.g. building new institutions and redesigning existing ones to undertake and coordinate these tasks]. Within this larger framework lie more strategic practices such as the creation of a Haiti Housing Trust Fund to leverage capital, including from innovative sources such as the large Haitian-American diaspora who are members of labor union pension funds.

Collaborators: J. Phillip Thompson (CoLab), Paul Altidore (The World Bank), Becky Buell (Oxfam), and Aseem Inam (MIT), with David Quinn, Amy Stitely, Krystal Peters, and Martha Bonilla

Indian Institute of Human Settlements: Bengaluru: 2009-2011

What is a radical new pedagogy for 21st century urbanism?

The Rockefeller Foundation partnered with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to develop a curriculum for the Indian Institute of Human Settlements [IIHS]. IIHS is a new pedagogical institution focused exclusively on addressing the rapid urbanization of 21st century India. The basic premise is that we need fundamentally new ways of researching and practicing in the new urban conditions of India [and other countries of the global south]. The production of knowledge is one of the most transformative forms of urban practice.

The focus was to prepare a curriculum for the Master of Urban Practice program. TRULAB Director Aseem Inam worked with MIT Professor Larry Vale to lead the design of the urbanism curriculum [i.e. city-design-and-building processes and their spatial products]. The team proposed a core of three parts: histories of urbanism: evolution of city form; theories of urbanism: values and actions; and urbanism practicum: analytical, design, and presentation skills. More advanced courses focus on four areas: urban systems: built and natural; urban development: private sector development; urban policy: regulating design; and urban regeneration: designing renewal.

This proposal was part of a larger global partnership, which gathered at a workshop in Bengaluru in 2010, including with University College London and the African Centre for Cities. The larger goal is to train urban practitioners in climate change adaptation and mitigation, economic development and financial management, energy policy and planning, environmental planning and design, law and governance, new urban planning, sociological foundations, technology and human settlements, transportation, and urbanism. IIHS has already been conducting radical new pedagogies, including in master classes in “unpacking urbanism” [e.g. understanding urban commons, and low-carbon cities].

Collaborators: Aseem Inam and Larry Vale (MIT), Aromar Revi and Kavita Wankhade (IIHS), Rockefeller Foundation.

Transforming Colonias: U.S.-Mexico Border: 2008

How does one design the transformation of low-income neighborhoods?

The firm, Moule & Polyzoides Architects and Urbanists, received a grant from the State of New Mexico to study low-income neighborhoods known as colonias on the U.S. side of the border. The goal was to propose strategies to transform these areas of poor infrastructure provision, exploitative housing costs, and poor design into livable neighborhoods. The starting point was to understand the true nature of the colonias by analyzing their architectural and urban forms, socioeconomic conditions, and legal and financial arrangements, including site visits and documentation.

Another step was to study existing housing affordability programs and policies by government agencies, non-profit organizations, private institutions, and individuals. Several transformative strategies emerged out of this collaborative and participatory process. One strategy was to prescribe general principles for redesigning the urbanism of the colonias, such as accessible locations, walkable layouts, connected street networks, small lots of land, and a range of housing types.

The team proposed and illustrated three levels of urbanist intervention: light [e.g. defining street edges], moderate [e.g. infill strategies], and full [e.g. establishing a new colonia]. The final part of the project was a set of detailed implementation strategies: a basic code governing the urbanism of the colonias, new regulations for the private housing market, creating nonprofit-owned affordable housing, increasing affordable homeownership opportunities, resident-controlled limited-equity ownership, and leveraging market-rate development.

Collaborators: Aseem Inam and Stefanos Polyzoides (Moule & Polyzoides Architects and Urbanists), Jesse Lawrence and Ken Hughes (State of New Mexico), Ruben Segura and Dwaine Solana (City of Sunland Park), Anapra Neighborhood Study Group (City of Sunland Park), J.O. Stewart (Stewart Holdings), Emily Talen (Arizona State University), and David Bergman (Economic Research Associates).

New City: Sunland Park: 2007-2008

How can designing a new city generate wealth creation?

The Downtown District, McNutt Corridor, and Border Crossing Master Plan was the design strategy, policy vehicle, and legal framework for the design of a new city in Sunland Park, New Mexico. At the heart of one of the largest international cross-border regions, the El Paso / Ciudad Juarez area, Sunland Park sits at the crossroads of the United States-Mexico border and at the juncture of three states: New Mexico, Texas and Chihuahua.

The primary goal of this strategic framework was to leverage design as a vehicle for wealth creation, an opportunity generated by a proposed border crossing and associated economic activities. The mode of practice adopted was immersive and multidisciplinary: an entire month was devoted to documenting and analyzing existing conditions, and the entire design team came together with community leaders and citizens for an intensive week-long charrette. The group focused on analyzing problems as well as assets.

The resulting framework focused on four key areas of the new city: Downtown District next to the Rio Grande River, McNutt Corridor consisting of residential and retail uses, the upgrading of the low-income Anapra Neighborhood, and the Border Crossing that also included transportation, warehouse and retail facilities. These were connected through a network of ecological corridors, public spaces and transportation systems. The 20-30 year process of implementation would be guided through legal and financial mechanisms [e.g. development codes, small business development]. These strategies are designed specifically to serve as catalytic platforms for wealth generation, especially for low-income communities.

Collaborators: Stefanos Polyzoides, Aseem Inam and Bill Dennis (Moule & Polyzoides Architects and Urbanists), David Bergman (Economic Research Associates), Kathy Poole (Biohabitats), Rick Chellman (TND Engineering), Jesus Ruben Segura, Gordon Cook, and Robert Ardovino (City of Sunland Park), and citizens of Sunland Park and surrounding areas.

Uptown Whittier Specific Plan: Los Angeles: 2006-2009

How can one generate pedestrian urbanism in the middle of automobile sprawl?

The team was selected in a competitive process because it was known for being extremely sensitive to contexts and for creating highly transparent city-design-and-building processes. Uptown Whittier is a 35-block historic retail core in the Los Angeles metropolitan region. The challenge was to develop mechanisms for attracting future investment to the area while significantly raising its overall quality of design and development. The key was to design a distinct pedestrian-oriented place.

The process began with a series of intensive individual and group dialogues with citizens, community groups, business leaders, city staff, and elected representatives. Such an open and participatory process was revolutionary for its context. A key aspect of this process was “introducing a community to itself,” in which existing problems and assets are presented to communities for corrective feedback, collective knowledge generation, and a common understanding of future possibilities.

Six catalytic strategies for Uptown Whittier emerged from this process: strengthening local retail and attracting complementary national retail chains, an efficient shared parking system, increasing in housing types and ownership patterns, harnessing church-based social services for affordable housing, social partnerships with Whittier College, and developing a sense of distinct identity through design guidelines, form-based codes, urban landscaping, and pedestrian amenities.

Collaborators: Stefanos Polyzoides and Aseem Inam (Moule & Polyzoides Architects and Urbanists), Jeff Collier and Steve Helvey (City of Whittier), David Bergman (Economic Research Associates), Paul Crawford (Crawford Multari & Clark Associates), Rick Chellman (TND Engineering), David Schneider (Fong Hart Schneider + Partners), James Schreder (Danjon Engineering, Inc), and Mayor, City Council, and citizens of Whittier.

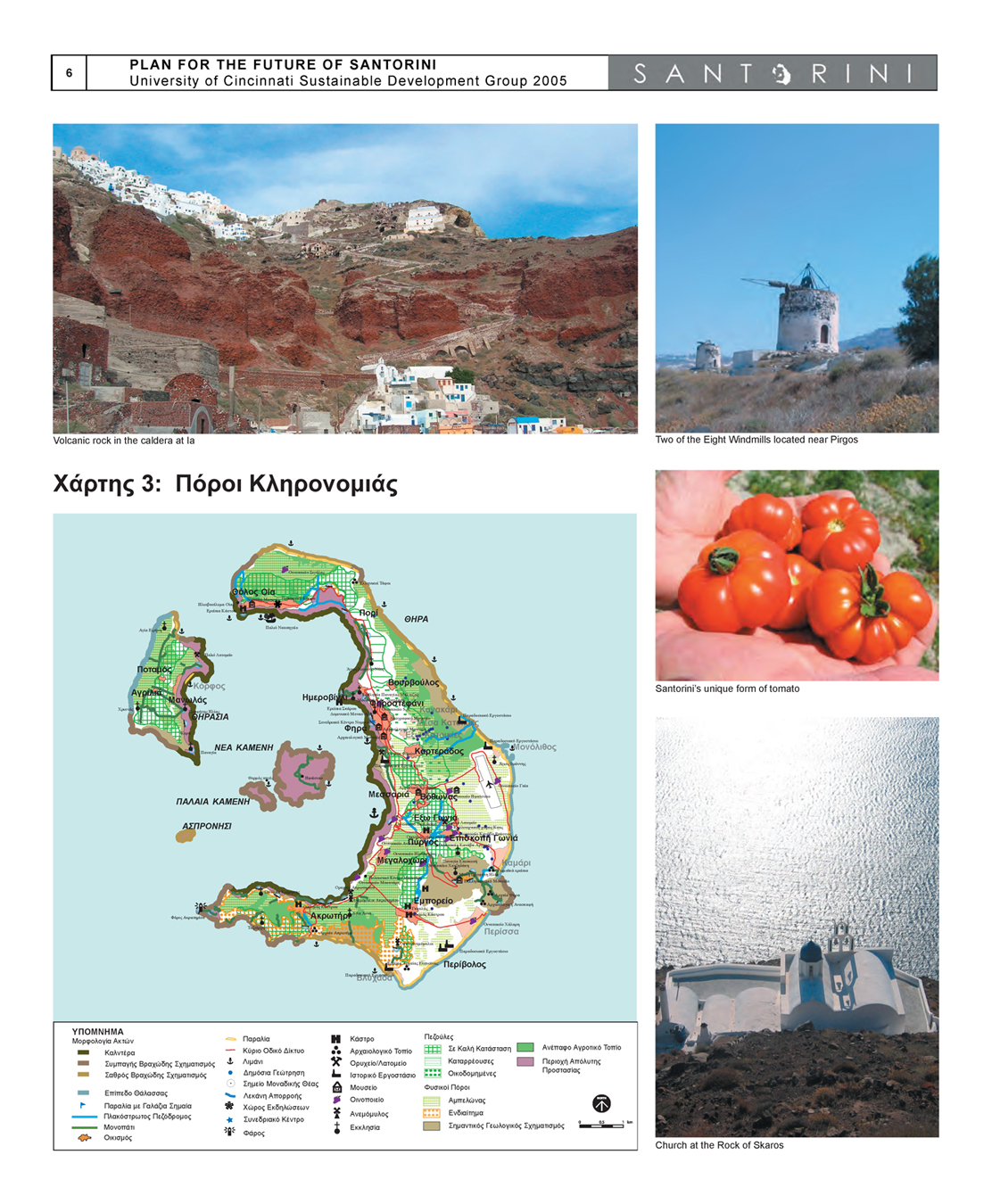

Plan For The Future of Santorini: Greece: 2004-2006

How can tourism focused development create a sustainably designed future?

Tourism has brought economic prosperity to one of the most beautiful group of islands in the world, collectively known as Santorini, in the South Aegean Sea. Tourism has also brought serious threats to its environmental and cultural heritage. The University of Cincinnati’s Sustainable Development Group worked with local individuals and organizations for 2 years, including spending time on the islands for 2 months each time for two consecutive summers.

Much like other TRULAB collaborations, the Santorini project began first and foremost with gaining a deep understanding of existing conditions in partnership with local stakeholders. These detailed studies and discussions led to a major proposal: for Santorini to become a Cultural Heritage Park, as a historical site of exceptional natural beauty that is not only recognized as such by the Ministry of Culture of Greece but also as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

The designation of Santorini as a Cultural Heritage Park was a strategy that enables an administrative and financial regime to protect and enhance its environment [e.g. volcanic topography, terraced landscapes, small scale agriculture, and archaeological sites from Cycladic pre-Minoan to ancient Greek to Venetian ruins]. A central feature of this strategy was a radically altered model of tourism that is small scale and low-impact, with an emphasis on agricultural, cultural, and water-related activities [e.g. harvest festival, open air performing arts, sailing].

Collaborators: Michael Romanos, Carla Chifos, Aseem Inam, and Frank Wray (University of Cincinnati - Sustainable Development Group), and Mayor Angelos Roussos, Vice Mayor Pothetos Metropias, Municipal Council, and Community Council of Thira, with Alexandra Aprili, Zachary Duvall, Christopher Dourson, John Hemmerle, Mark Kinne, Aubrey Longnecker, Allison Maume, Andrew Meyer, Chrissy Scarpitti, Eleni Sourtzi, Rae-Leigh Stark, Craig Yacks, Michael Yerman, and Idil Yilmaz

Michigan at Trumbull: Detroit: 2000

Is it possible to transform a neighborhood within a shrinking city like Detroit?

The purpose of the 5-day workshop in January 2000 was to brainstorm and articulate ideas for the future of the old Tiger Baseball Stadium, located at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull Avenues in Detroit. The team of urbanists, architects, landscape architects, city planners, urban historians, public artists and community leaders immersed themselves in the area by living and working there. A series of debates, studies and design exercises led to a set of principles to drive the strategy.

One of the principles was to acknowledge the large size of the area by working with different precincts, from a regional magnet incorporating the old Michigan Central Railway Station down to a mix of infill housing types carefully placed within surviving neighborhoods amid the abandonment. Another principle was to build upon local strengths, such as the area’s easy access to civic amenities and economic opportunities, the potential to adaptively reuse regional landmarks like Tiger Stadium and Michigan Station, and to extend the small yet thriving residential neighborhood of Corktown.

Following from these principles, the next one proposed the creation of a regional magnet such as large scale retail, which was badly needed in the area. Another crucial principle was to transform large amounts of vacant land into an opportunity for consolidation into vegetation corridors, public spaces and community gardens. Part of this strategy would be to foster experiments in urban agriculture and land banks. In all these ways, the area could become a model for a new Detroit. In fact, in the years since the workshop, many of these ideas have come to fruition.

Collaborators: Alex Krieger (Chan Krieger Associates and Harvard University), Aseem Inam (University of Michigan), Office of the Mayor and Planning and Development Department (City of Detroit), and Corktown Citizens District Council, with Carmen Bigles-Raldiris, Delbert Brown, Filip Geerts, Malik Goodwin, Shawn Holyoak, Il Kyung Kwon, Dawn Lenitz, Ginger Murphy, Lee Poechmann, Randal Reakof, and Ruchita Varma

Washington Avenue Plan: St. Louis: 1991-2011

How can policy changes revive a post-industrial city’s abandoned downtown?

In the early 1990s, the City of St. Louis began efforts to revive the central city area. Part of this effort was led by the St. Louis Development Corporation [SLDC] to study the future potential of Washington Avenue, a street lined with many buildings that served as warehouses for the St. Louis garment district. These large multi-story buildings, with brick, stone and terra cotta facades, were largely abandoned after World War II. The SLDC team took up the challenge by considering these buildings collectively as the urban public realm, rather than as individual architectural projects.

The Washington Avenue Plan, completed in 1992, became truly effective a few years later as part of two other policy initiatives: one was its registration in the National Register of Historic Places [which helped highlights its value as a historic district] and the other was an urban investment initiative called the Downtown Now! Development Action Plan. Together, these public policy initiatives [along with a historic rehabilitation tax credit program] worked to attract private investment, especially residential and commercial development, into the area over a period of 20 years.

The Downtown Now Plan focused on the transformation of the avenue’s streetscape by expanding public amenities, adding and improving street lighting and furnishings, and enhancing sidewalks for a pedestrian-friendly design. The street redesign prioritized alternative transit opportunities by maintaining a shared-use bicycle lane and two subterranean light rail stations. As a result of these policy initiatives over time, Washington Avenue was named a “Great Street” by the American Planning Association in 2011.

Collaborators on the initial Washington Avenue Plan: Don Royse, John Hoal, Steven Van Gorp, Elva Rubio, and Aseem Inam (St. Louis Development Corporation and Washington University), and others

India Habitat Centre: Delhi: 1989-1993

How does one design cities by redesigning institutions?

The India Habitat Centre [IHC] is a revolutionary project for the city. Led by the pioneering architect, environmentalist and urbanist Joseph Stein, the project was a collaboration between S.K Sharma, Chairman of the Government of India’s Housing and Urban Development Corporation [HUDCO] and the Stein’s firm, Stein Doshi Bhalla Architects & Engineers. The project is revolutionary in several ways, as an ecological campus, as a partnership between agonistic actors, and as a vibrant urban hub, especially when the project was originally conceived in the India of the late 1980s.

Rather than pursue the model of the traditional stand-alone government building, Stein and Sharma decided to make it a medium-height campus organized around courtyards. The courtyards created micro-climates through the use of shading devices, landscaping and water to help keep them cool in the searing Indian heat. These courtyards also serve as passages between buildings, thus creating opportunities for social interaction among the public, private and non-profit organizations [including those opposed to government policies] occupying IHC.

The ecological campus is also a vibrant urban hub. One reason is through the model of sharing: shared parking, shared meeting spaces, shared eating areas, and other shared facilities for the different organizations working on urban, housing and infrastructure issues. Another reason is the presence of facilities and activities such as topical conferences, public talks, art exhibits, and music and dance performances. In this manner, the design of the institutional structures and the material spaces of IHC interweave to create a transformative project for Delhi.

Collaborators: Joseph Stein, Anurag Chowfla, Meena Mani, Aseem Inam and others (Stein Doshi Bhalla), S.K. Sharma (Housing and Urban Development Corporation Ltd)

Rural Habitat Development Programme: Gujarat: 1986-present

How can a rural habitat program provide lessons for urban transformation?

The pioneering Rural Habitat Development Programme was initiated by the Aga Khan Planning and Building Services India, part of the global Aga Khan Development Network. The initial mandate was to design and building housing for the rural poor in the state of Gujarat to stem the flow of migrants to informal settlements in Indian cities such as Mumbai. However, extensive research [including field work in the villages] resulted in two radical shifts.

The first radical shift that emerged from the research was a shifting from designing houses to addressing more critical challenges around housing such as finance, infrastructure and community mobilization. The second shift to emerge, especially from the dialogue with rural communities, was to work in partnership with village residents. The resulting rural habitat development framework consisted of long-term strategies that relied on responding to changing circumstances, collective knowledge, collaborative action, and field testing of ideas.

The program, which continues today nearly 30 years after its inception, has now benefitted over 100,000 people, including in other parts of India. By adapting to changing circumstances, the program has lead to efforts in housing rehabilitation, earthquake reconstruction, water and sanitation systems, and other environmental health infrastructure issues. The effectiveness of this long-term, adaptive and partnership approach provides valuable insights into potential processes of urban transformation.

Collaborators: Original program design and operation by Aseem Inam, Nasser Munjee, Habib Thariani and others (Aga Khan Planning and Building Service India), and residents of the villages of the Saurashtra region in the state of Gujarat, India

![Concluding thoughts from the case study analysis of the Säynätsalo Town Hall in Jyväskylä [Finland]. Source: Aseem Inam, 2016.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51a8f326e4b08c2bc46d7c14/1574348305279-51SNLGKJJGVM1HH2AHHX/Consequences+of+Design+Concepts.PNG)

![The three-step process of the workshop used questions to provoke individual and varied responses and strategies based on the unique context of each city [rather than imposing a top-down one-size-fits-all best-practices approach]. Source:  ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51a8f326e4b08c2bc46d7c14/1435268504005-Z2RENL5M908J94PP0FP0/Figure_3-PPT_slide-3_step_process.jpg)

![An image showing the praca flutuante [i.e. floating square] on the left, the ferry in the foreground, and the new public space--the large pier with permanent spaces for the provision for social services. Source: Jeff Chicarelli and Gabrie](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51a8f326e4b08c2bc46d7c14/1434053559968-HZQDPYSFLROF3Z676E02/P2P_image04.png)

![The epicenter of the 2010 Haitian earthquake was the capital city of Port au Prince, which destroyed thousands of buildings, especially housing. The team addressed medium-term [i.e. provide immediate shelter] and long-term [i.e. design housing](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51a8f326e4b08c2bc46d7c14/1434139291007-52QE3JHYFMUROQWLQHNS/Figure_1-Haiti_recovery-earthquake_damage-small.jpg)

![The research-based practice revealed that a key challenge in the housing deficit in Haiti [even more than housing finance, design or construction materials] was the issue of land titling. Thus, a key recommendation of the final proposal was to](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51a8f326e4b08c2bc46d7c14/1434139293298-TBM9ZYTD8MEZ9HZBE8XH/Figure_4-Haiti_recovery-land_titling-small.jpg)

![The final set of implementation strategies look to learn from [rather than blindly emulate] other housing affordability efforts, such as resident-controlled limited-equity ownerships like the Sawmill Community Land Trust in Albuquerque. Source: ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51a8f326e4b08c2bc46d7c14/1434491195510-JX5KWSNBARMDZVX7QIAG/Figure_4-Sawmill_Community_Land_Trust-small.jpg)

![A central feature of the design framework for the new city was the use of ecological corridors [e.g. in the hills and along the Rio Grande River] and interconnected walkable streets that constitute everyday public space [e.g. in the residential neig](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51a8f326e4b08c2bc46d7c14/1434576070572-5JRZVQOXDSQ5XF4WT8CA/Figure_3-ecological_framework-SP-small.jpg)

![In the plan, design strategies and implementation mechanisms are intertwined. One example is the use of carefully-researched and much-debated design guidelines [e.g. for contemporary architectural styles] to raise the overall quality of develo](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51a8f326e4b08c2bc46d7c14/1434576276529-GSVW9EJ9H72QPNY92HT6/Figure_2-Uptown+Whittier-design_guidelines.jpg)

![Another example of intertwining design strategies with implementation strategies is to provide enough detail [e.g. of bioretention basins, tree wells and diagonal parking] such that the plan can be implemented with great ease. Source: Mo](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51a8f326e4b08c2bc46d7c14/1434576277113-ZEE6YDI46QWDEL7T3AUW/Figure_3-Uptown+Whittier-landscape_details-small.jpg)

![The ultimate legacy--and implementation strategy--of the Uptown Whittier Specific Plan is the creation of an active political constituency of citizens who advocate for the kind of pedestrian urbanism [e.g. compact, walkable and mixed-use] they deser](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51a8f326e4b08c2bc46d7c14/1434576279072-OYY20SENTYTY4ELXUBHT/Figure_4-Uptown_Whittier-final_presentation.jpg)