Beyond Objects: City as Flux

“What really exists is not things made but things in the making. Once made, they are dead, and an infinite number of alternative conceptual decompositions can be used in defining them. But put yourself in the making by a stroke of intuitive sympathy with the thing and, the whole range of possible decompositions coming at once into your possession, you are no longer troubled with the question of which of them is absolutely true. Reality falls in passing into conceptual analysis; it mounts in living its own undivided life—it budges and bourgeons, changes and creates.”

— William James, A Pluralistic Universe (New York: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1909), pages 263-264.

The following case studies are analyzed via the theoretical framework of "beyond objects: city as flux."

Duisburg Landscape Park, ruhr valley, germany

The Ruhr Valley, in western part of Germany has been in a constant state of change. Throughout processes of deindustrialization, the Ruhr Valley experienced severe decline. In order to transform the region, a publicly funded project commenced with the design of an industrial landscape park from 1989 to 2002. The project was aimed at achieving spatial, social, and economic restructuring. The resulting Duisburg Landscape Park is an effect of this transformation from industrial to post-industrial Germany. Its success derives directly from its engagement with many forms of flux. As such, it is exemplary of the ways in which memory can be transformed by design practices that engage not only the three-dimensional material object, but also the crucial fourth-dimension of time.

The park is designed, produced, and activated through interaction. As illustrated in the accompanying images, since the great monumental structures are free for anyone to interpret or reinterpret their connection to place, memory, heritage, etc., the structures’ meanings exist in a state of flux. Thus, the Duisburg Landscape Park begins to illustrate the way in which the object of the park works within a larger framework of transformation of the Ruhr Valley. Significant to this is the dialectical relationship of the park at present, the steel manufacturing plant of the past, and their respective social contexts. In this way, the Duisburg Landscape Park goes beyond the “the project as an object” and begins to represent the region, city and site as being in the making or experiencing perpetual change.

**Case study analyzed by Ernest Haines

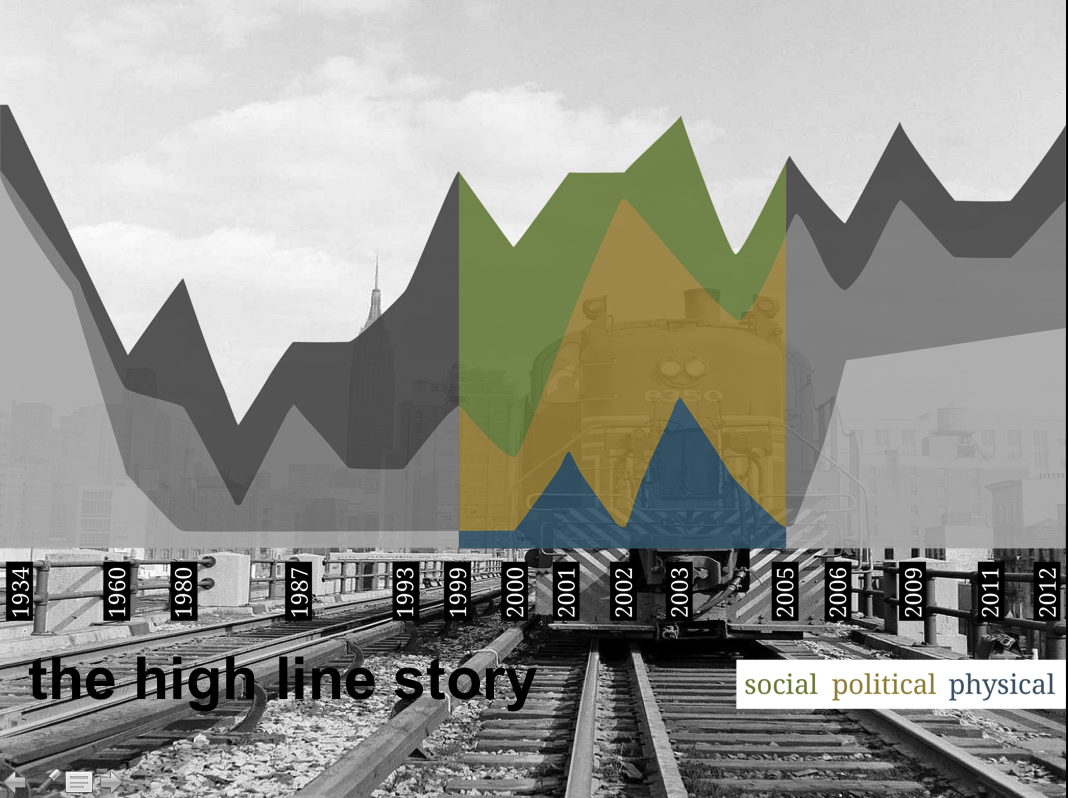

The High Line, New York

The High Line in NYC is an example of designing the city as flux. By viewing the HL from the perspective of city as flux, the most salient feature that emerges is the system that created the project, and that will carry its design forward. It's less about designing a physical intervention, and more about designing the social networks, coalitions, policies, and organizations that get the project implemented, and will sustain it in perpetuity.

The High Line is a public park built on an historic freight rail line elevated above the streets on Manhattan’s West Side. It is owned by the City of New York, and maintained and operated by Friends of the High Line. Founded in 1999 by community residents, Friends of the High Line fought for the High Line’s preservation and transformation at a time when the historic structure was under the threat of demolition. It is now the nonprofit conservancy working with the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation to make sure the High Line is maintained as an extraordinary public space for all visitors to enjoy. In addition to overseeing maintenance, operations, and public programming for the park, Friends of the High Line works to raise the essential private funds to support more than 90 percent of the park’s annual operating budget, and to advocate for the preservation and transformation of the High Line at the Rail Yards, the third and final section of the historic structure, which runs between West 30th and West 34th Streets.

The High Line is located on Manhattan's West Side. It runs from Gansevoort Street in the Meatpacking District to West 34th Street, between 10th and 11th Avenues. The first section of the High Line opened on June 9, 2009. It runs from Gansevoort Street to West 20th Street. The second section, which runs between West 20th and West 30th Streets, opened June 8, 2011.

*Case study analyzed by Veronica Acosta and Laura Guzman.

MIT Experimental Design Studio, Boston

How can one train future urbanists to engage with and design the city as flux? In 2009, an experimental urbanism studio at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Boston tested the notion of design as a verb, a becoming and unfolding process, similar to the art of comedy improvisation (i.e. comedy improv), such that it fosters playful interactions among different ideas, strategies, interventions, scales, and materials, and injects strategic influxes of creativity at key points in the evolution of a project. As the designer and professor of the studio, I developed the comedy improv pedagogy based on my training and performance in comedy improv in Hollywood, years of professional experience in urbanism, and prior teaching experience with other kinds of experimental studio pedagogies. In addition, two of the most well regarded books in comedy improv served as references: Truth in Comedy: The Manual of Improvisation, and Improvise: Scene from the Inside Out. Scholarly research on the uses of improvisation to create innovation, including in business administration and computer design, also aided in crafting the pedagogical experiment.

The project was to develop a design strategy for a 9-block area undergoing rapid change and located just south of the Chinatown area, near downtown Boston. The final strategy that emerged out of the studio process included programming human activities and related land uses, design of public spaces, integration of natural elements such as vegetation and water in a highly urbanized area, adaptive reuse of existing structures, and long term phasing of adaptation and implementation in the face of changing circumstances. The project was actually a vehicle for experimenting with comedy improv as a design methodology for urbanism.

Al-Azhar Park, Cairo

The Al-Azhar Park is a 74-acre (30 hectare) public park located in the eastern part of Cairo, a city of 18 million people, near the Al-Azhar Mosque. For hundreds of years, household garbage and building debris accumulated at the Park’s site, creating the 130 foot (40 meter) high Al-Darrassa Hills. The Park cost $30 million and opened to the public in 2005. Sasaki Associates of Boston carried out the preliminary master planning studies, and the final landscape architecture design was the work of the firm Sites International of Cairo, with Maher Stino and Laila El-Masry Stino as the principals.

The implementation of the Park design required innovation and adaptability in other ways. According to Maher Stino, one of the principal landscape architects, “almost everything installed in the park was custom made by local artisans and craftsmen,” from the benches to the light fixtures to the bollards. With very few large landscape architecture projects happening in Egypt, “there were no landscape furniture manufacturers in Egypt or professional plant nurseries to supply the plant palette we wanted,” he explained. They were able to turn these challenges into opportunities by establishing off-site plant nurseries on land supplied by the American University in Cairo and by conducting site furniture workshops in the adjacent Darb Al-Ahmar neighborhood.

What is remarkable is that through deliberate efforts in this process, young people from the neighborhood have been trained in restoration and related skills such as stone work and carpentry, skills that are in high demand in Egypt. The Aga Khan Trust’s operation of the Park and the continuing restoration of historic monuments have provided training for over 1,000 people in the neighborhood. Job training and employment opportunities are also being offered in other sectors such as shoemaking, furniture manufacturing and tourist goods production. Apprenticeships are available for automobile electronics, mobile telephones, computers, masonry, carpentry and office skills. Hundreds of young men and women in Darb Al-Ahmar have found work in the Park, in horticulture and on project teams restoring the Ayyubid Wall.

Olympic Village, Barcelona

Even though the design of the Olympic Village in Barcelona is usually regarded as a one-time designed three-dimensional set of urban objects completed in 1992, it is in fact part of a much longer-term process of urban transformation of the city of Barcelona. Two dates are particularly influential: 1888, when the World’s Fair was used to radically redesign a part of the city, a legacy of leveraging international events to radically redesign the city that continues to this day; and 1976, when the General Metrpolitan Plan inaugurated a longer-term, more spatially dispersed and formalized planning process.

The master plan for the Olympic Village was prepared by the private firm, MBM Puidomènech, with principals Oriol Bohigas, David Mackay and Albert Puigdomènech, and implemented by a public firm was created in 1986, the Vila Olímpica Societat Anònima. When first completed in 1992, the Olympic Village was christened Nova Icària, but today, the project is more commonly known as Vila Olímpica (Olympic Village), and the larger area within which it is located is called Poblenou.